The Newcomer’s Guide to Cyber Threat Actor Naming

I was driven by a deep frustration when I started my public “APT Groups and Operations” spreadsheet in 2015. I couldn’t understand why I had to handle so many different names for one and the same threat actor.

Today, I understand the reasons for the different names and would like to explain it so that newcomers stop asking for a standardization. Off the record: by demanding a complete standardization you just reveal a lack of insight.

But let’s start from the beginning: As we all know, vendors name the threat actors that they track. Some of them just use numbers like Mandiant/FireEye, Dell SecureWorks or Cisco Talos and others like Kaspersky, CrowdStrike or Symantec use fancy names and naming schemes that create an emotional, figurative or mythological context.

We secretly love these names.

They shed a different light on our work — the tedious investigation tasks, the long working hours, the intense remediation weekends and numerous hours of management meetings. If the adversary is Wicked Panda, Sandworm or Hidden Cobra, we perceive ourselves as some kind of super heroes twarthing their vicious plans. These names create an emotional engagement.

The following table, which is a tab in my public spreadsheet, shows naming schemes used by the different vendors:

In contrast to people that actually work in this field, many non-specialist voices frequently criticize vendors for a number of reasons. They lament the lack of standardization, overconfident attribution and believe to recognize biased reporting depending on the vendors home country. Most of this criticism is unjustified.

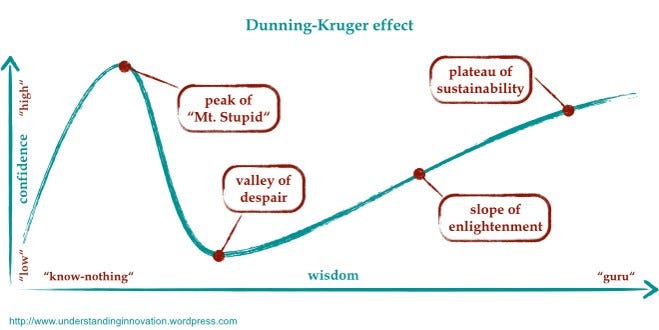

Frankly, I believe that if they had a deeper understanding of the indicators that led to an attribution or the reasons for different names they would immediately dive into the “valley of despair”.

I see myself slowly climbing the “slope of enlightenment”, learning every day from many researchers that I admire and respect. In a short article like this I cannot provide a deeper understanding of the indicators that led to a certain attribution, but I can work out the different reasons that lead to different names and naming schemes.

As you can see in my spreadsheet, numerous names exist and mapping them is often imprecise and sometimes flawed. But I had to start somewhere and a partly incorrect mapping is better than having no mapping at all. (others may disagree)

There are “human”, “technical” and “operational” reasons that lead to all the different names. The following section lists most of these reasons categorized by their type.

These are the major “human” caused reasons for naming confusions:

- An operation name is used as the threat actor name (e.g. Electric Powder)

- A malware name is used as threat actor name (e.g. NetTraveler)

- Vendors miss to relate to other vendors research (e.g. missing link from TEMP.Zagros to MuddyWater)

- Journalists are unwilling to correct wrong mapping in public articles (e.g. NBC claiming that APT 37 is Labyrinth Chollima)

These are the major “technical” reasons why names diverge:

- Every vendor sees different pieces of the full picture (different TTPs / IOC clusters: sample sets, C2 infrastructure etc.)

- Threat actors join forces or split up

- Groups share their toolsets with others (e.g. Winnti malware)

- Groups share their C2 infrastructure with other groups (e.g. OilRig with Chafer)

This leads to the following problems:

- A vendor tracks multiple groups where another vendor sees only a single group (a single group named Mirage or Vixen Panda is tracked as two separate groups by FireEye)

- Two operations are falsely attributed to a single group (example: ScarCruft & DarkHotel with Operation Erebus & Operation Daybreak)

- Operations are attributed to a group based on a part of the IOC cluster that a different vendor maps to another group (e.g. operations by Chafer group falsely attributed to OilRig based on the shared C2 infrastructure)

But there are also less technical and more “operational” reasons that lead to different names:

- By using the name of another vendor, one may resent that decision later if the other vendor takes it in a direction that one disagrees with. As vendors have collected and constantly receive different pieces of the puzzle, agreeing on a mutual name always bears the risk of diverging TTPs. Maintaining one’s own name provides flexibility and the option to go down different routes.

- By using another vendor’s name one would implicitly admit that the research of the other vendor is more complete and could be seen as the basis of one’s own research. While discoverers of comets rush to report the new celestial bodies in order to obtain the right to name them, vendors often track new actors for months before publishing the first report. You often lose a tactical advantage by reporting too soon or too much. It’s a trade-off between that tactical advantage and a reputation gain. Reporting first doesn’t mean that the research is foundational or more thorough and therefore other researchers don’t see it as entitlement to assign a name.

As you can see, many reasons lead to different names. The standardization of threat actor names is not as easy as it sounds. The Antivirus industry confronts the same critics since many years and cannot comply with the demands for very similar reasons.

I wouldn’t release vendors from all responsibility. It is still crucial that they keep linking their research to the research of others, pointing out partial or full IOC overlaps and alignments with previously reported operations based on the respective TTPs. Otherwise, mapping the different threat actors names becomes an irresolvable task.

APT Groups and Operations Spreadsheet (HTML version)

Mentioned abbreviations:

IOC = Indicator of Compromise

TTP = Tools, Tactics, Procedures

APT = Advanced Persistent Threat

C2 = Command and Control

NBC article with errors: